Under Pressure or Unprepared?

Was the cause of the U.S. Women's National Team's poor result at the 2023 FIFA Women's World Cup pressure or a lack of preparation?

Under Pressure, the Netflix documentary that follows the U.S. Women’s National Team’s throughout 2023 while centering on the team’s FIFA Women’s World Cup performance, opens with an audio montage of media personalities as well as players and even head coach Vlatko Andonovski criticizing, chastising and condemning the team’s performance.

As the audio montage concludes, Fox studio analyst Alexi Lalas says, “It’s not just about losing a game. The big risk is that they become irrelevant.”

We then see U.S. Women’s National Team players sit down in preparation of explaining themselves to the camera - and by extension to us - throughout the remainder of the four episodes with Lalas’s comment alongside the film’s title “Under Pressure” hanging over the rest of the documentary.

But is the possibility of the U.S. Women’s National Team’s irrelevancy the best question to focus on in this moment? And is the idea that the pressure on this team was too great to bear accurate?

I’ll give you that they are sensational questions, that they are lightning rods, that they elicit reaction. But no, to me they’re not the best questions to focus on - even after the team’s worst performance and worst result at a FIFA Women’s World Cup.

Why?

Because for the former, it’s absurd to think that one poor result, even one lackluster four-year cycle can answer whether the U.S. Women’s National Team will become irrelevant. That question fails to acknowledge that the team has a 30+ year history of excellence from results, to breaking societal boundaries to being of cultural interest. True, things can tumble down quickly, but only the next 8-12 years can tell if this poor result and this lackluster four-year cycle are the start of a downfall or just an outlier.

And the danger in zeroing in on the latter question - was the pressure too great for this team - is that the question obscures the truth: Given hindsight, it is clear that there was no way this edition of the U.S. Women’s National Team was going to win the 2023 FIFA Women’s World Cup. The pressure of trying to live up to the standards of its predecessors and win a third consecutive World Cup had nothing to do with it.

Rather when I look back on how this team - emphasis on “team” - took the field for the 30 games leading up to the 2023 FIFA Women’s World Cup and the resulting four matches they played in the tournament, I see a crystal clear example of an adage from legendary UCLA men’s basketball coach John Wooden: “Failing to prepare is preparing to fail.”

The grit and determination of the individual players on this team plus the luck of the goalpost got them past Portugal and onto the Round of 16 where the individual players again gave a valiant effort before falling in a penalty kick shootout to Sweden. This in a tournament where failing to advance out of the group stage would have been a fair result based upon the team’s preparation.

Here is why.

1. How minutes were distributed in the build up to the World Cup

When the World Cup roster was released, much was made of the 2023 team having 14 players making their World Cup debut - tops all-time outside of the initial 1991 Women’s World Cup team - with just 9 players returning to the World Cup stage. But in terms of preparing for the 2023 FIFA Women’s World Cup, that breakdown can be misleading as it can be interpreted that the 9 returning players were the core of this team both in its preparation for the World Cup and also at the tournament. This was not the case. Consider of the 9 returning players:

- Crystal Dunn and Julie Ertz were each away from the team for a significant portion of the build up to the 2023 FIFA Women’s World Cup with pregnancies.

- Kelley O’Hara and Megan Rapinoe, each in their 4th World Cup, transitioned into non-starting roles.

- For the five remaining returning players only Lindsey Horan was a sure thing throughout the build up to the tournament in terms of predicting she would start at the 2023 FIFA Women’s World Cup. (Horan played the second most minutes of any player during the build up). For the others consider:

- Casey Murphy earned more minutes in goal during the build up to the World Cup than Alyssa Naeher (1,260 to 1,170).

- Alex Morgan was left off of the roster for seven matches at the end of 2021 into 2022 due to both a request off for time to rest and coaching decisions.

- Emily Sonnett was in a battle for playing time throughout the build up to the World Cup and the tournament itself.

- Rose Lavelle did not play in two of the three 2023 She Believes Cup matches in February and then injured her knee in an April 8 match against Ireland which caused her to miss the team’s final two preparatory matches and be on limited minutes during the World Cup.

All of this uncertainty in who would form the core of the team led to much more competition for both starting spots and minutes during the 2023 World Cup cycle than is typical. This competition in turn led to less time for players to settle into clearly defined roles and for the starting lineup to jell headed into the World Cup.

The best way to wrap your head around this is to visualize it.

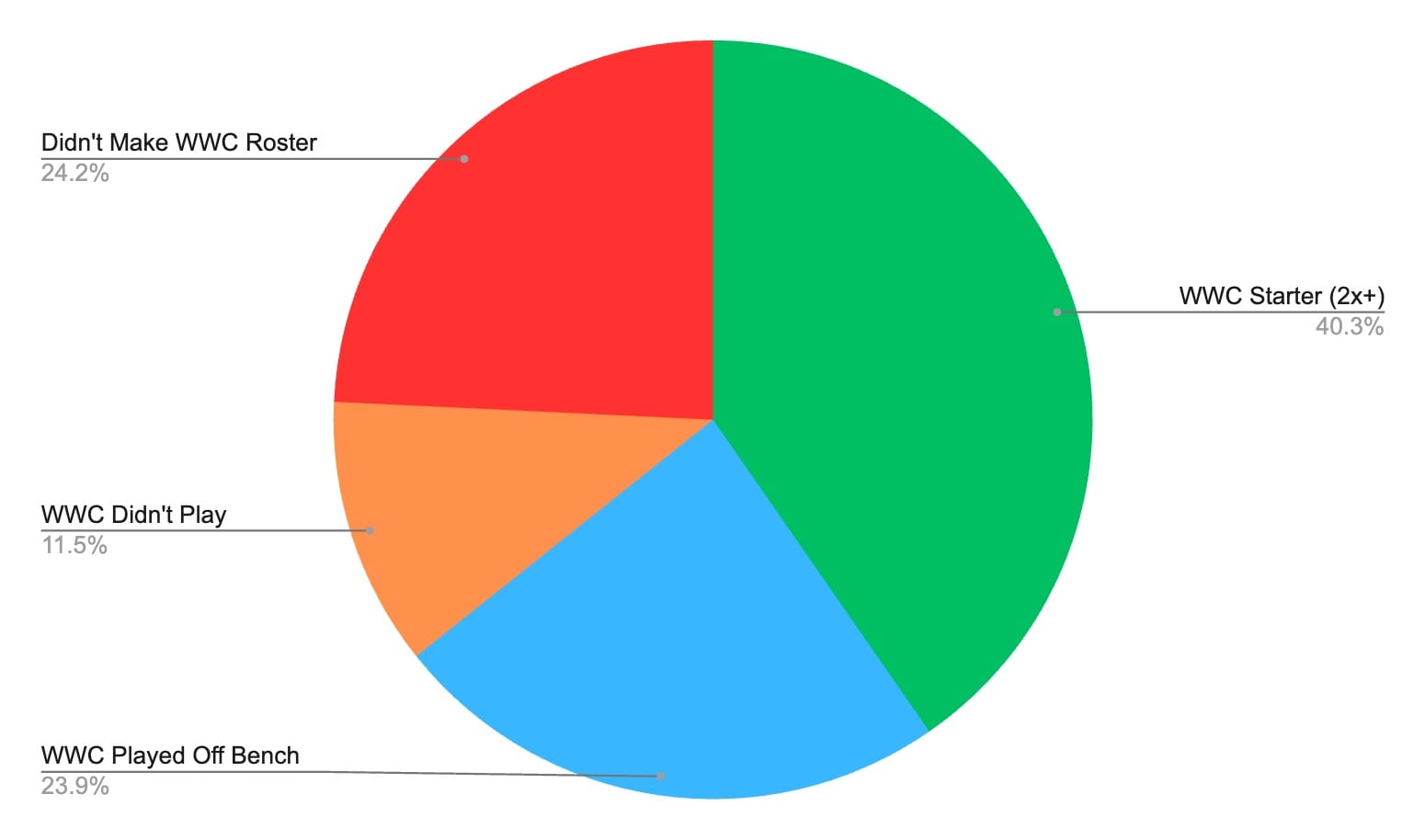

Let’s start by looking at how the total minutes available in the build up to the 2023 FIFA Women’s World Cup were distributed among:

- Players who started at least twice at the World Cup (Green)

- Players who came off the bench or started at most once during the World Cup (Blue)

- Players who made the roster but did not play any minutes at the World Cup (Orange)

- Players who did not make the World Cup roster (Red)

Goalkeepers have been removed from this analysis to 1) focus on how the field players were prepared and 2) typically one goalkeeper starts the entirety of the World Cup with the other two not playing any World Cup minutes which skews the visualization. (More on the methodology of creating these visualizations can be found here.)

How does this pie chart for 2023 compare to the same visualization of how the total minutes available were distributed in the build up to every other World Cup dating back to 1999?

Unfavorably. Consider:

- Players who earned 2 or more starts in the World Cup only received 40.3% of the playing time prior to the 2023 FIFA Women’s World Cup, which was the lowest percentage by far. The 2003 team comes in second to last with 50.7% while every other squad had 63-70% of the available minutes in the build up to the World Cup go to the players who wound up starting at least twice at the tournament.

- What’s the other similarity between the 2023 and 2003 squads? The percentage of minutes that went to players who didn’t make the World Cup team. 24.2% of the available minutes in the 2023 cycle went to players who were not named to the World Cup team, while 26.2% of the 2003 cycle minutes likewise went to players who didn’t make the World Cup team. Every other World Cup team had only 9-15% of the available minutes in the World Cup cycle go to players who didn’t make the roster.

- Players who made the 2023 World Cup roster but didn’t take the field at the actual tournament received 11.5% of the available playing time in the build up to the World Cup. This is the highest percentage by far in the World Cup cycles I evaluated with every other World Cup team having only 0-4.6% of the available build up minutes go to players who made the World Cup roster but didn’t play at the tournament.

Want to see the full analysis with visualizations of how minutes were distributed in the build up to every World Cup dating back to 1999? View them here.

Why did so few minutes in the build up to the 2023 FIFA Women’s World Cup go to players who started at least twice and so many minutes go to players who didn’t make the roster?

Injuries, unsurprisingly as most fans know, were a big factor. Just over half of the red pie slice in the 2023 pie chart - representing the pre-World Cup minutes for players who didn’t make the World Cup roster - are the minutes for three 2019 World Cup veterans - Abby Dahlkemper (back), Becky Sauerbrunn (foot) and Mal (Pugh) Swanson (knee) - as well as up-and-coming forward Catarina Macario (ACL).

Maternity leaves factored in as well. As they returned from pregnancies, World Cup starters Dunn and Ertz played just 16.2% and 2.6%, respectively, of the total minutes available to any individual player during the build up to the World Cup. (There were 2,700 available minutes - 30 matches at 90 minutes apiece - for any individual player to log during the build up to the 2023 FIFA Women’s World Cup.)

And so did coaching decisions. Alana Cook (1st on the team with 72.2% of pre-World Cup minutes available played), Sofia Huerta (8th, 55.6%) and Ashley Sanchez (12th, 42.4%) were all heavily invested during the build up to the World Cup but Huerta was the only one to see any playing time at the World Cup and just 7 minutes at that.

2. How individual players were prepared to play defined roles at the World Cup

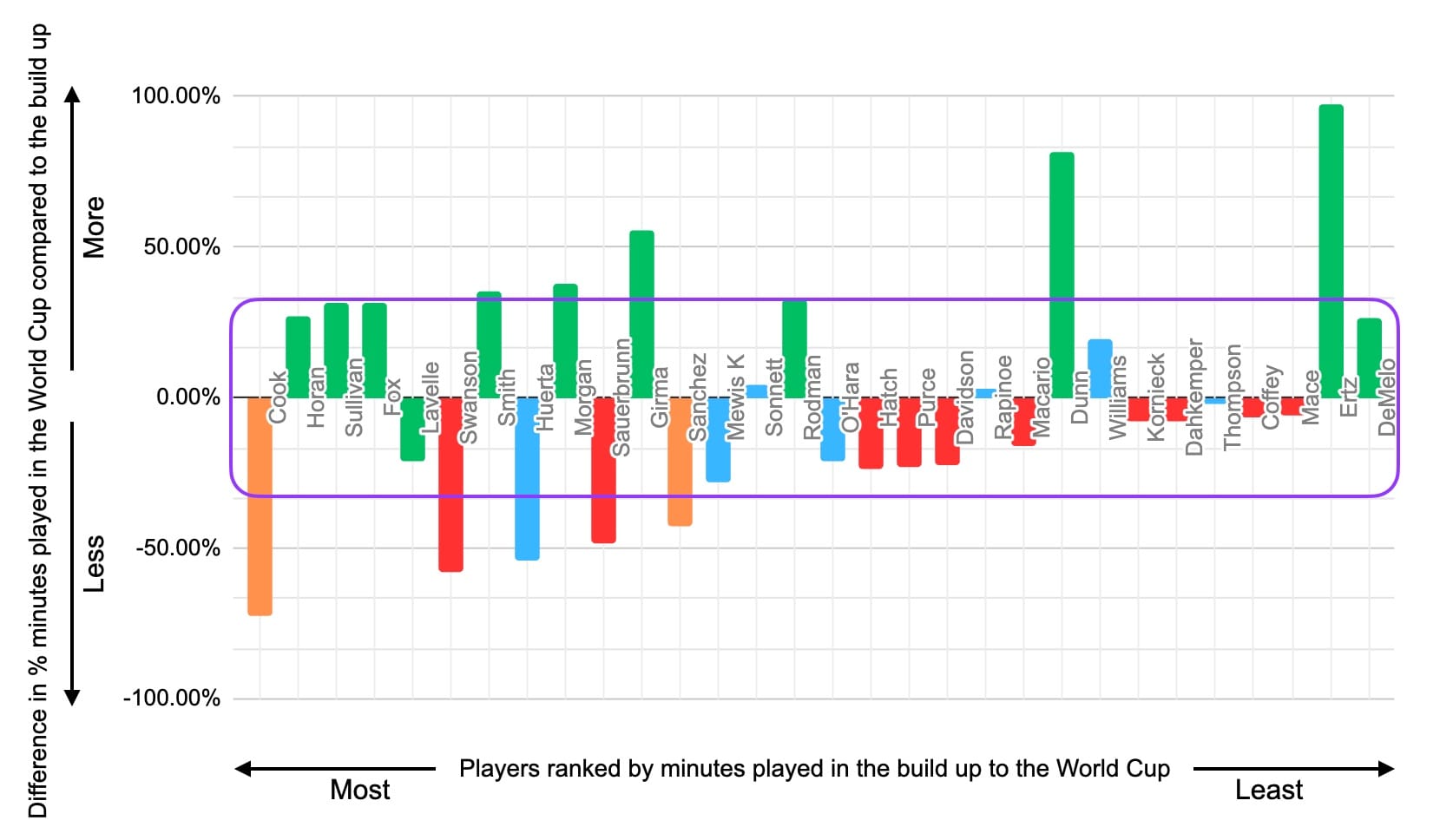

The significance of the differences in percent of playing time for individual players between the World Cup itself vs the build up to the tournament become more obvious when viewed visually. And here is why looking at the differences in players’ percents of playing time during the World Cup vs the build up to the tournament matters - it speaks to whether individual players had defined roles that held true in the preparation for the tournament as well as the tournament itself. Were individual players ready to take on their World Cup roles based upon the role they played on the team in the build up to the tournament?

Warning: the following graph and explanation of it gets geeky. If your eyes start glazing over, move on to the third and final visualization.

On the following graph, the top 28 field players in terms of minutes played during the build up to the 2023 FIFA Women's World Cup are listed in rank order left to right with Ertz (33rd in minutes played across all players who saw minutes in the build up to the World Cup) and Savannah DeMelo (37th) added at the far right. The colors of the bars continue to reflect the same categories that were applied to the pie charts above (green for 2x starters, blue for players who primarily came off the bench, orange for players who saw no minutes at the World Cup and red for players who did not make the World Cup roster).

The height of each field player’s bar indicates the difference between the percent of available minutes the player logged at the World Cup minus the percent of available minutes logged in the build up to the World Cup. If the player’s bar is above the x-axis, they played more minutes percentage wise in the World Cup than in the build up (i.e. Ertz) and similarly, if the player’s bar is below the x-axis, they played less minutes percentage wise in the World Cup than in the build up to the tournament (i.e. Cook). If a player’s bar is close to 0% (i.e. Sonnett, Rapinoe or Alyssa Thompson), they played a similar percentage of minutes available in both the World Cup and the build up to the tournament.

As the World Cup is such a smaller sample of games (4 matches for the 2023 squad) vs the build up to the tournament (30 matches for the 2023 squad), some difference is expected - i.e. a player logs every minute at the World Cup but only 70% of the available minutes in the build up to the tournament. Due to this, I’d consider anything within a +/- range of 33% normal and the purple rectangular box drawn on top of the graph reflects this consideration of a +/- 33% difference.

For the 2023 squad, notice how many individual field players saw a significant difference in their percent of available minutes played at the World Cup in comparison to the build up to the tournament, which is reflected by the bars that eclipse the purple rectangular box. There are 10 players who eclipsed this mark with 8 of these players surpassing the +/- 33% mark by five percentage points or more.

How does this compare with every other World Cup squad dating back to 1999?

- The 2003 squad (yep, them again!) had 9 players exceed a +/-33% difference in percentage of minutes played in the World Cup vs the build up to the tournament.

- The rest of the U.S. World Cup teams from 1999-2019 had 4 or 5 players eclipse a +/- 33% difference with the 2019 team just barely having 3 players exceed this threshold.

Want to see the visualizations of the difference in percentage of minutes played in the World Cup vs the build up to the tournament for individual players in each World Cup dating back to 1999? View them here.

Returning to the 2023 team - Beyond the injuries, the maternity leaves and the coaching decisions affecting individual players, there are factors that influenced the distribution of minutes during the build up to the 2023 FIFA Women’s World Cup that are much more difficult to quantify such as:

- Core transition. The 2023 World Cup cycle was bound to be a transitional one with the core of the 2015 and 2019 winning squads exiting their prime. Ten field players - Morgan Brian, Ertz, Tobin Heath, Ali Krieger, Carli Lloyd, Alex Morgan, O’Hara, Christen Press, Rapinoe and Sauerbrunn - took on pivotal roles on those championship teams with only Morgan (and perhaps Sauerbrunn until injury derailed her) under consideration for starting roles prior to the 2023 FIFA Women’s World Cup until Ertz returned to the team three months prior to the tournament.

- Player identification & development. With the 2023 roster being a transitional one - from one championship producing generation to hopefully the start of the next - player identification & development were crucial. Who are the players who can step onto the world stage and immediately make a difference? What is the system between youth clubs, NWSL clubs, international club scouts and U.S. Soccer that supports the identification and development of players well before a World Cup cycle begins to step into this moment? In late 2021 and the first portion of 2022, head coach Vlatko Andonovski told the media he needed time to evaluate younger players and gave them considerable minutes in National Team games vs more established players. Was this evidence of the player identification & development system working or not? Either way, the approach Andonovski took resulted in less time for starting player roles to be identified and established prior to the 2023 FIFA Women’s World Cup, which was only exacerbated by…

- The pandemic. With COVID-19 delaying the Tokyo Olympics from 2020 to 2021, all teams who competed at both the Tokyo Olympics and 2023 FIFA Women’s World Cup had one less year to prepare for the latter. With the U.S. Women’s National Team going through a major player transition, the lost year cost them an additional 15-20 matches which would have given the coaching staff more time to identify and invest in the projected 2023 World Cup starters.

All of these factors - the injuries, the maternity leaves, the coaching decisions, the core roster transition, the gaps in the player identification and development system, the pandemic - resulted in a lack of stability for the U.S. Women’s National Team starting lineup throughout the World Cup cycle.

3. When was the core of the World Cup team identified? How many matches did the nucleus of the team have together to build an identity headed into the World Cup?

To visualize this, I looked at when each individual field player who earned two more more starts at a World Cup (the players in green in the previous visuals) began taking on a core role on the team in the build up to the World Cup. What match number in the build up to the World Cup did the player begin to regularly start and then continue to do so through the rest of the build up? (More on the methodology for creating this visualization can be found here.)

Here is how this graph looks for the 2023 team. The x-axis shows the number of matches during the build up to the World Cup. The green bars associated with each field player who started twice or more at the World Cup indicate the span of matches in the build up to the World Cup where the player regularly started.

Notice how three players - DeMelo, Ertz and Rodman - did not take on major roles with the team until they became starters for the first game of the World Cup. Historically, this isn’t the norm for the U.S. Women’s National Team. With the exception of the 2003 team (yep, them again!), every other edition of the National Team had the core group of players who would start twice or more at the World Cup identified at least six matches in advance of the start of the tournament.

Another indicator of the 2023 team not being prepared to make a deep run at the World Cup: every other National Team dating back to 1999 had at least seven field players who would go on to start twice at the World Cup taking on a core role by the midway point of the build up to the tournament. The 2023 team only had five identified at the midway point and by the last match of the build up to the World Cup, still only had seven of the 10 field players who would go on to start twice or more at the World Cup taking on a core role. No other National Team edition failed to identify at least 10 field players who would start twice or more at the World Cup prior to the tournament.

Want to see the visualizations of how the nucleus of each World Cup squad came together during the build up to each tournament dating back to 1999? View them here.

It is harsh to judge the 2023 edition of the National Team given the combination of factors they faced between the injuries, the maternity leaves and the major core player transition they needed to go through in an abbreviated timeframe due to the pandemic. I don’t think any U.S. World Cup team has been dealt a more challenging hand of cards.

Still having seen these three visualizations and knowing how they compare to past World Cup teams, is it any surprise that this 2023 team lost in the Round of 16? That this team barely advanced out of its group?

How far would you predict this team would advance? Would you give them any chance of winning the World Cup? Would you predict they would fail to make it out of their group?

A lot gets made of individual player form - Is she at the top of her game? Is she peaking for the World Cup? Is she ready to make a statement? And yes, individual player form is important. But I would argue that team form, the preparation of the collective to perform together at their peak capability, is just as important.

The 2023 World Cup edition of the U.S. Women’s National Team had no identity, no chemistry and no rhythm on the field - all things that are needed to advance in and win a World Cup. But how could they given the team’s preparation?

With hindsight, I’d suggest a more appropriate title for the Netflix documentary on the 2023 squad - Unprepared: The U.S. Women’s National Team.

Given This, How Do I Feel About the Future of the National Team?

Optimistic!

I don’t see anything to be dooming and glooming about. Preparation is something that can be addressed. There is a head coach in Emma Hayes coming in who everyone is raving about, and we will see what approach she takes to evaluating the player pool, identifying and developing players, and establishing player roles and team identity and chemistry. Knock on wood, the injury bug will go away. And there is a lot of strong, young talent who either got a taste of the World Cup in 2023 or who already started to get a look with the National Team at the end of 2023.

As the National Team players say, LFG!

Extra Time: The Culture Debate

Following the U.S. Women’s National Team’s 0-0 draw in their final group match against Portugal, where the team got lucky to advance out of their group at the 2023 FIFA Women’s World Cup as a 91st minute Portuguese shot bounced off the right post, U.S. players were captured on the field dancing in celebration of advancing to the knockout stage of the tournament. Fox studio analyst and former National Team star Carli Lloyd criticized the players behavior, mindset and performance.

“I have never witnessed something like that,” Lloyd said on the post-game Fox broadcast, which was also highlighted on the Netflix documentary. “There’s a difference between being respectful of the fans and saying hello to your family. But to be dancing, to be smiling - I mean, the player of that match was that post. You’re lucky to not be going home right now.”

Lloyd’s comments in turn spurred a range of reactions from current and former National Team players as well as fans and other commentators.

What’s my take on the debate over whether the U.S. Women’s National Team has lost its way in terms of the team’s culture?

First cultures evolve over time. Whether we’re talking about American society, a company, a family or a team like the U.S. Women’s National Team, culture is going to evolve with time. That doesn’t imply that the change is going to be good or bad, simply that it’s going to happen. I don’t expect anyone’s culture to remain static.

Second, I think it’s all in the eye of the beholder.

For me as a long-time fan of the team, I can understand the disdain former players who have invested years in the National Team may have over the current team’s perceived culture and the perceived lack of adherence to the standards of old. When I was younger (i.e. in my 20s) and saw the world through a much more dualistic lens, I would have been picking a side of the debate and adamantly arguing it.

Over the years, I’ve been learning that dualities - right/wrong, good/bad, black/white, etc. - fail to grasp the human experience. With age and perhaps a little more wisdom, my hope for myself and for others is to feel it all, experience it all, embrace it all. Include rather than exclude.

So give me the real, human feeling of joy in moving on in a tournament where you also lament that you haven’t played well; give me the real, human reaction of being in disbelief at your beloved team celebrating a disappointing result; give me the real, human experience of laughing through sad tears at the absurdity of missing a penalty kick.

It all belongs.